C2.6: Domestic market

C2.6.1 Introduction

Organic products are sold through a variety of outlets, such as supermarkets (i.e. multiple retailers), independent shops including specialist organic shops, artisan food producers (e.g. bakers and butchers), farmers markets, farm shops and by mail order.

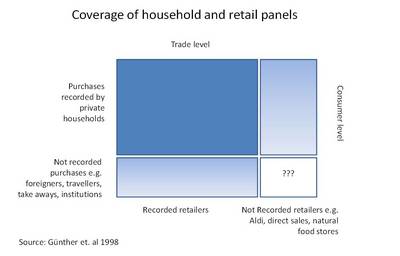

All of the data collection approaches described below have the weakness that they do not cover the full organic market. Household panels show the whole variety of marketing channels, but with different coverage rates. Retail panels based on electronic point of sale (EPOS) data focus on sales in participating multiple retailers and other outlets that use scanners at check-out. Retail sales through non-multiple channels can be important in the organic market (up to 40% of all organic sales in some countries). Sales through direct marketing through farm shops and weekly markets or sales through independent and specialist organic shops can be difficult to track without conducting specific surveys unless specific panels exist. The challenge of achieving good coverage of all sales channels, and thus a reliable estimate of the total organic market, is discussed further below.

C2.6.2 Approaches

Different sources are used to estimate the sales values in specific outlets and of the total domestic market, as well as the breakdown by product, and include:

- household panels,

- retail panels (multiple retailers, specialist panels of independent/organic shops in some countries),

- surveys of retailers,

- surveys of farm shops and farmers’ markets,

- expert estimates.

C2.6.2.1 Household panels

Household panels use a number of households that track all their purchases. Data are now mostly collected with the help of digital scanners, where consumers scan the EAN code (European Article Number/International Article Number or bar code) of their food purchases at home (Niessen, 2008). Products such as loose vegetables and fruit, unpacked cheese, bread or eggs, etc. that do not carry an EAN code need to be scanned by the consumer separately and manually at home; using a code book.

Table C.2-2: Advantages and disadvantages of household panels

| Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|

Since household panels do not involve face-to-face interviews, the social motivation to overestimate organic purchases is less than with interview based data (Schantl, 2004; Michels, 2004). | There may be missing data on products consumed before they could be scanned, such as take-away meals, coffee and other beverages and also purchases from household members other than the main shopper (Buder, 2011; Niessen, 2008). |

| Household panels provide quantitative data of all purchases, collected over long time periods and therefore allow trends to be analysed (Schantl, 2004). | There may be a lack of full coverage for specific marketing channels. Also, coverage may be problematic for specific products that are seen as socially undesirable (e.g. alcohol, sweet snacks). Coverage is also poor for loose products (without EAN code) such as fruit, vegetables, and bakery products because of the need to manually enter (Niessen, 2008). |

| Companies providing such data, very often record socio-demographic variables for their panel members and so it is possible to obtain information about the households and purchasing behaviour (Schantl, 2004). | “Panel effects” can occur, whereby the act of noting their purchases over long periods of time causes consumers to alter their shopping behaviour (Schantl, 2004). |

| Comparison of organic and non-organic food retail is easier, as the same panel and method can be used for both (Michels, 2004). | Organic products often have a lower coverage in the panel than conventional products as organic consumers tend to not be the “transparent costumer” and more rarely take part in household panels (Bien and Michels 2007). |

| Classification mistakes of the organic status, more by householders occur more frequently in products bought in direct sales (Niessen and Hamm, 2006). |

Source: Gerrard et al. (2014) based on various studies

Panels are selected to be representative of the total food market. Even in the most well developed organic markets, such as that of Germany, the organic food market covers less than 10% of the total food market. Because of the small size of the organic market relative to the total market, the number of households recording organic purchases in a specific product category can be very small (depending on the size of the panel). Small errors, for example in product classification, could potentially have a large distorting impact on the total value of the organic food market when panel data are extrapolated to the total organic sales data. Furthermore, it is known that a relatively small proportion of households account for a relatively large proportion of total spending in the organic food market (e.g. 20% of households account for 80% of spending in the UK (Buder et al., 2010; SA/WDA/OCW, 2004). This distribution can only partially be explained through demographic variables (such as education, age, income). If, in the composition of such a panel, the number of high spending organic households is over- or underrepresented, significant errors in estimating the total market value could occur.

A number of studies have been carried out in Germany to further explore the use of household panel data in estimating the organic market. Bien and Michels (2007) carried out a study of 500 households from a German panel, who were asked to keep additional records of their organic purchases in addition to the panel returns. The authors, on behalf of ZMP (Central Market and Price Report Office) and the panel company GfK, used these data to develop a specific methodology for fresh products to minimise misclassifications, based on checking price differences. For purchases of fresh products, a data check is used such that they are only accepted as organic if their price is higher than the specific non-organic threshold price, set on the basis of the monthly price reporting published in Germany.

A study conducted by Niessen and Hamm in 2006 analysed the mistakes made by German consumers when classifying conventional products as organic, and found that older householders without children tend to make more mistakes in this area than other respondents. The researchers found that consumers made most mistakes (around 35%) when buying the products through direct sales, on-farm sales, or markets. More than 70% of all classifying mistakes made in egg sales occurred when eggs were bought through direct marketing, with the percentage being even higher for strawberries and for potatoes. Around 5-15% of the products bought in supermarkets or discounters were classified wrongly.

C2.6.2.2 Retail panels

Retail panels provide data on purchases at the point of the retailer themselves, rather than the consumers. Such data is often based on EPOS (electronic point of sales) and hence restricted to outlets that use electronic check-outs. Some EPOS data may cover all of the supermarkets in a country: especially where they are relatively few in number, whereas others may only cover those that are willing to cooperate with the marketing research company. Some out-of-house sales (e.g. coffee shops) may also be covered.

Table C.2-3: Advantages and disadvantages of retail panels

| Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|

| All sales in participating outlets are recorded. | Not all retail chains are taking part (e.g. ALDI); no coverage of independent retailers. |

| Retail panels provide quantitative data, collected over long time periods and therefore allow trends to be analysed. | Errors of classification of organic status when retailers set up their EPOS system will be carried through into the panel data. Some organic foods may be incorrectly recorded as non-organic and vice versa. |

| Comparison of organic and non-organic food is straightforward, as they are collected with the same instrument. | Data from such panels is generally only available at a cost, as these are commercial panels carried out by market research companies. |

| Compared to household panels, they cannot give information about the consumers. | |

| There is no possibility to differentiate between household purchases and purchases of restaurants, snack bars etc. That is why retail panels tend to overestimate the sales of participating supermarket chains to consumers. |

Source: Gerrard et al. (2014), based on Michels (2004) and Bien and Michels (2007)

Retail panels can be a valuable data source in estimating the total organic sales value. They have the advantage of covering nearly 100% of EAN-coded products and participating supermarkets. They also give a direct comparison of organic and non-organic market values, but they do not cover direct sales and may have gaps in coverage of the independent sector. Furthermore, they do not cover sales of loose fresh products that are not bar-coded.

The case studies of Germany and France in the OrganicDataNetwork report (Gerrard et al., 2004) showed that specialist retail panels for organic shops provide data on this sector in Germany and in France.

- Example

In Germany, the Nielsen retail panel covers only packaged products and not all supermarkets take part. It therefore covers only approximately 30% of the German organic market. In countries with a higher share of supermarkets, such as Denmark, Sweden, the UK or Switzerland, this share would be higher but some sales channels outside the supermarkets such as natural food stores, direct sales, online sales are not covered.

C2.6.2.3 Surveys among retailers

A good coverage of the organic market can be achieved via a survey of retailers in countries where supermarkets and other retail outlets play a major role in the sale of organic products. Compulsory surveys will get a good coverage rate, but it may also be possible to get information from retailers on a voluntary basis: although coverage should be carefully considered in this case. Surveys may also be a good instrument to cover sales through independent shops that are not covered by retail panels. Another option may be to study the annual reports of the supermarket chains, which give information on the total retail sales of organic products in some countries.

- Examples

Such a survey, which includes a survey on organic products, is carried out in Denmark by the Danish Statistical Office and in Sweden by Statistics Sweden (SBC), and covers a large part of the market in these countries. The surveys are compulsory but excluding catering sales and direct marketing. In Denmark, once the surveys have been evaluated, different forms of quality checks are performed and, respondents are sometimes contacted for further questions (Statistics Denmark, 2014).

In the UK, a survey of most major multiple retailers, restricted to the total turnover in the organic market (but not broken down by product categories), is carried out annually by a trusted third party and the results are one of several sources used to estimate the total value of retail sales the UK Organic Market Report, which is published annually by the Soil Association.

C2.6.2.4 Surveys of farm shops and farmers’ markets

Data on sales through farm shops and farmers’ markets are more commonly collected by surveys of producers, because they tend to be not covered by any other data source. Brown (2002) reviewed research on farmers’ markets in the USA from 1940 to 2000 and identified some methodological issues in carrying out research into direct sales; including the possibility of over-looking small producers. Furthermore, censuses and surveys often rely on farmers’ memory and farmers’ openness and so may be open to error (she quoted other researchers who found that farmers tend to understate rather than overstate sales). She also reviewed the various attempts that had been made to assess the economic value of direct sales, and demonstrated the large discrepancies that can arise as different methods are used to extrapolate data from a sample to state level (Brown, 2002). All of these issues apply to assessing the organic sales through farmers’ markets and farm shops with the additional problem of having to separate out organic sales from non-organic sales.

C2.6.2.5 Expert estimates

Expert estimates of the organic market, or a specific sector, can provide additional information for the purpose of cross checking of data and trends and thus can be one source for obtaining an estimate of the total organic market. However, , they should only be used as the only data source if no other data collection method (panel data or surveys) exists or can be carried out. If using experts, it is necessary to carefully select experts for specific market segments (e.g. meat, dairy, arable) and cross-check estimates against other data sources (e.g. production volume, see above). The bases of expert estimates are usually surveys of retail chains or wholesalers to get an idea of the market.

- Example

In Estonia, the market for locally produced products is estimated based on a rather detailed survey of specialised organic shops and other shops selling organic products and organic producers/processors. The overall organic domestic market value is based on very rough estimation based on information collected from the shops and is probably not very accurate. Domestic market value data are published very late, more than a year later. As market data appear so late, the Estonian Centre for Ecological Engineering makes its own small surveys on estimated changes in retail sales from one year to another.

C2.6.3 Concluding remarks

The usual case is that no data source (panel or survey) covers all sales channels or all product groups. It remains therefore challenging to obtain a reliable figure of the total organic market value and volume in a country.

The graph below illustrates the issue of the different coverage rates in the different kinds of panels.

In many countries a puzzle approach has to be used to mix different sources to obtain a market estimate. The examples of Germany and France are described in detail in the Case Study Report (Gerrard et al, 2014).

The study of Bien and Michels (2007) provides some insights into suitable methods of weighting results of different German panels to estimate the total organic market value. This relies on the cross-checking of data from the different panels with other sources (including expert estimates).

Data from all panels are generally only available at a cost, as these are commercial panels carried out by market research companies.

Household and retail panel data include information about all food products: not just organic products. Each organic product line has to be classified as such in order to be recorded and retrieved separately. Errors in classification can occur both at the level of data analysis in the data houses (mainly for bar-coded product lines), and at the level of the household-panel members (shoppers) for non-bar-coded products.

To allow comparison of trends for different product categories over time and between countries a common classification system needs to be adopted. The OrganicDataNetwork recommends adopting the Statistical Classification of Economic Activities in the European Community as the main classification system for the products traded (Eurostat, 2012). If Eurostat classifications are not detailed enough, it is always possible to extend the classifications.

When buying either retail or household panel data as part of obtaining an estimate of the organic market, the OrganicDataNetwork suggests discussing the following questions with the panel institution:

- Participants:

- Which outlets (supermarket chains) take part in the retail panel?

- How many households participate in a household panel and how are they selected?

- Coverage:

- What would the panel institution estimate to be the coverage for the single sales channels (including single supermarket chains)?

- What would the panel institution estimate to be the coverage for the different product groups?

- What would the panel institution estimate to be the coverage for organic food compared to conventional food?

- Organic product classification:

- How does the panel institution check whether products are organic or conventional?

- Can product classification be mapped against the Eurostat CPA code?

- What are the quality control routines?

With these questions it is easier to assess the quality of panel data: especially for estimating the organic market. Similar questions also make sense when buying data for the development of single products or product groups.

This website was archived on January 11, 2020 and is no longer updated.

This website was archived on January 11, 2020 and is no longer updated.